The van Kampen theorem#

Suppose a space \(X\) is decomposed as the union of a collection of path-connected open subsets \(A_\alpha\), each of which contains the basepoint \(x_0 \in X\). By the remarks in the preceding paragraph, the homomorphisms \(j_\alpha:\pi_1(A_\alpha)\rightarrow \pi_1(X)\) induced by the inclusions \(A_\alpha \hookrightarrow X\) extend to a homomorphism \(\phi : {\Large *}\pi_1(A_\alpha)\rightarrow \pi_1(X)\). The van Kampen theorem will say that \(\phi\) is very often surjective, but we can expect \(\phi\) to have nontrivial kernel in general. For if \(i_{\alpha \beta}:\pi_1(A_\alpha \cap A_\beta) \rightarrow \pi_1(A_\alpha)\) is the homomorphism induced by the inclusion \(A_\alpha \cup A\beta \hookrightarrow X\), so the kernel of \(\phi\) contains all the elements of the form \(i_{\alpha \beta}(w)i_{\beta \alpha}(w)^{-1}\) for \(w \in \pi_1(A_\alpha \cup A_\beta)\). Van Kampen’s theorem asserts that under fairly broad hypotheses this gives a full description of \(\phi\):

Theorem 1.20. If \(X\) is the union of path-connected open sets \(A_\alpha\) each containing the basepoint \(x_0 \in X\) and if each intersection \(A\alpha \cup A_\beta\) is path-connected, then the homomorphism \(\phi : {\Large *}_\alpha \pi_1(A_\alpha) \rightarrow \pi_1 (X)\) is surjective. If in addition each intersection \(A_\alpha \cup A_\beta \cup A_\gamma\) is path-connected, then the kernel of \(\phi\) is the normal subgroup \(N\) generated by all elements of the form \(i_{\alpha \beta}(w)i_{\beta \alpha}(w)|^{-1}\) for \(w \in \pi_1(A_\alpha \cup A_\beta)\), and hence \(\phi\) induces an isomorphism \(\pi_1(X) \approx {\Large *}_\alpha \pi_1(A_\alpha)/N\).

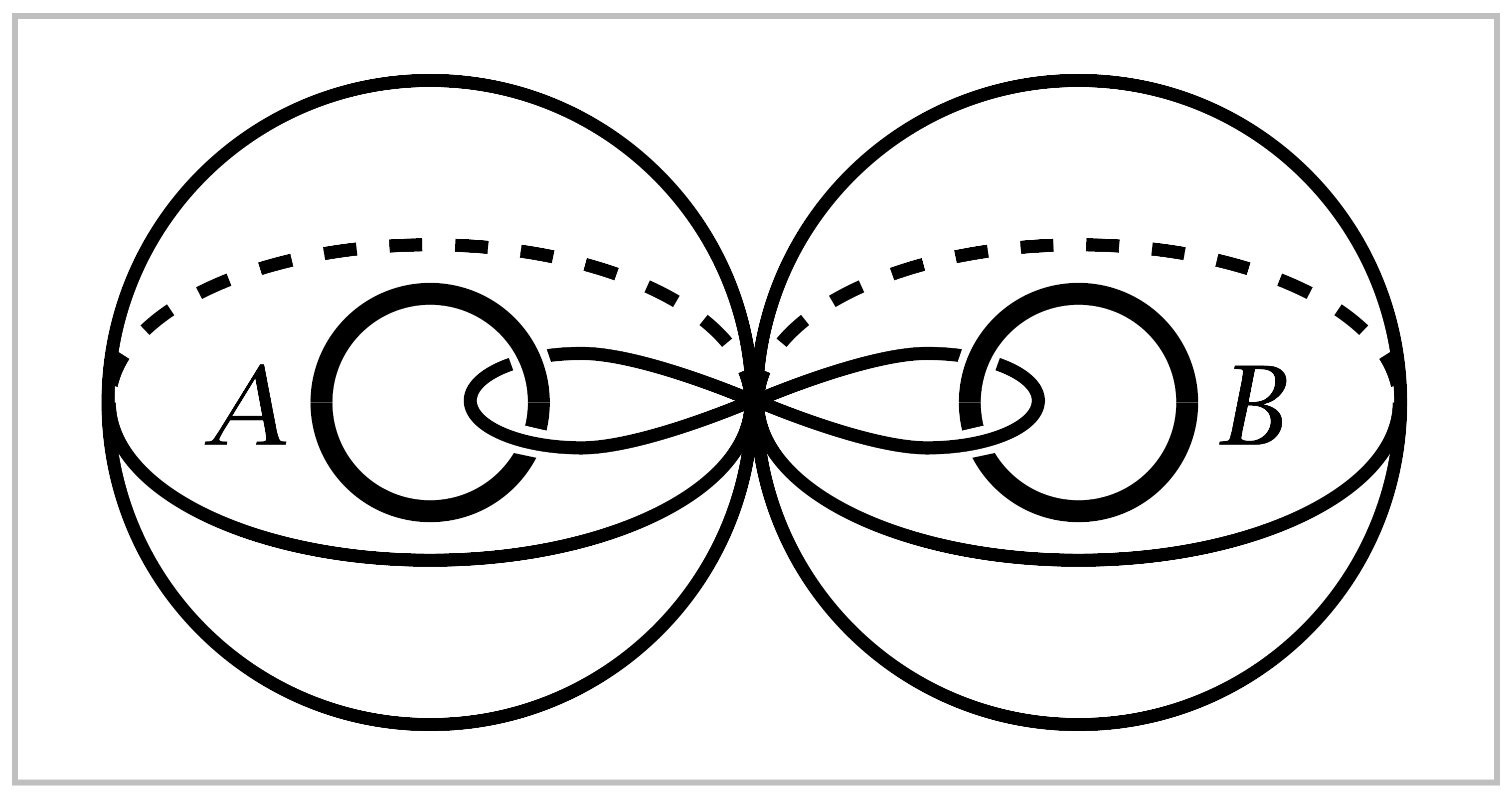

Example 1.21: Wedge Sums. In Chapter 0 we defined the wedge sum \(\bigvee _\alpha X_\alpha\) of a collection of spaces \(X_\alpha\) with basepoints \(x_\alpha \in X_\alpha\) to be the quotient space of the disjoint union \(\coprod _\alpha X_\alpha\) in which all the basepoints \(x_\alpha\) are identified to a single point. If each \(x_\alpha\) is a deformation retract of an open neighborhood \(U_\alpha\) in \(X_\alpha\), then \(X_\alpha\) is a deformation retract of its open neighborhood \(A_\alpha = X_\alpha \bigvee _{\beta \neq \alpha}U_\beta\). The intersection of two or more distinct \(A_\alpha\)’s is \(\bigvee_\alpha U_\alpha\), which deformation retracts to a point. Van Kampen’s theorem then implies that \(\phi: {\Large *}_\alpha \pi_1(X_\alpha)\rightarrow \pi_1(\bigvee_\alpha X_\alpha)\) is an isomorphism, assuming that each \(X_\alpha\) is path-connected, hence also each \(A_\alpha\).

Thus for a wedge sum \(\bigvee_\alpha S^1_\alpha\) of circles, \(\pi_1(\bigvee_\alpha X_\alpha)\) is a free group, the free product of copies of \(\mathbb{Z}\), one for each circle \(S^1_\alpha\). In particular, \(\pi_1(S^1\vee S^1)\) is the free group \(\mathbb{Z}*\mathbb{Z}\), as in the example at the beginning of this section.

It is true more generally that the fundamental group of any connected graph is free, as we show in §1.A. Here is an example illustrating the general technique.

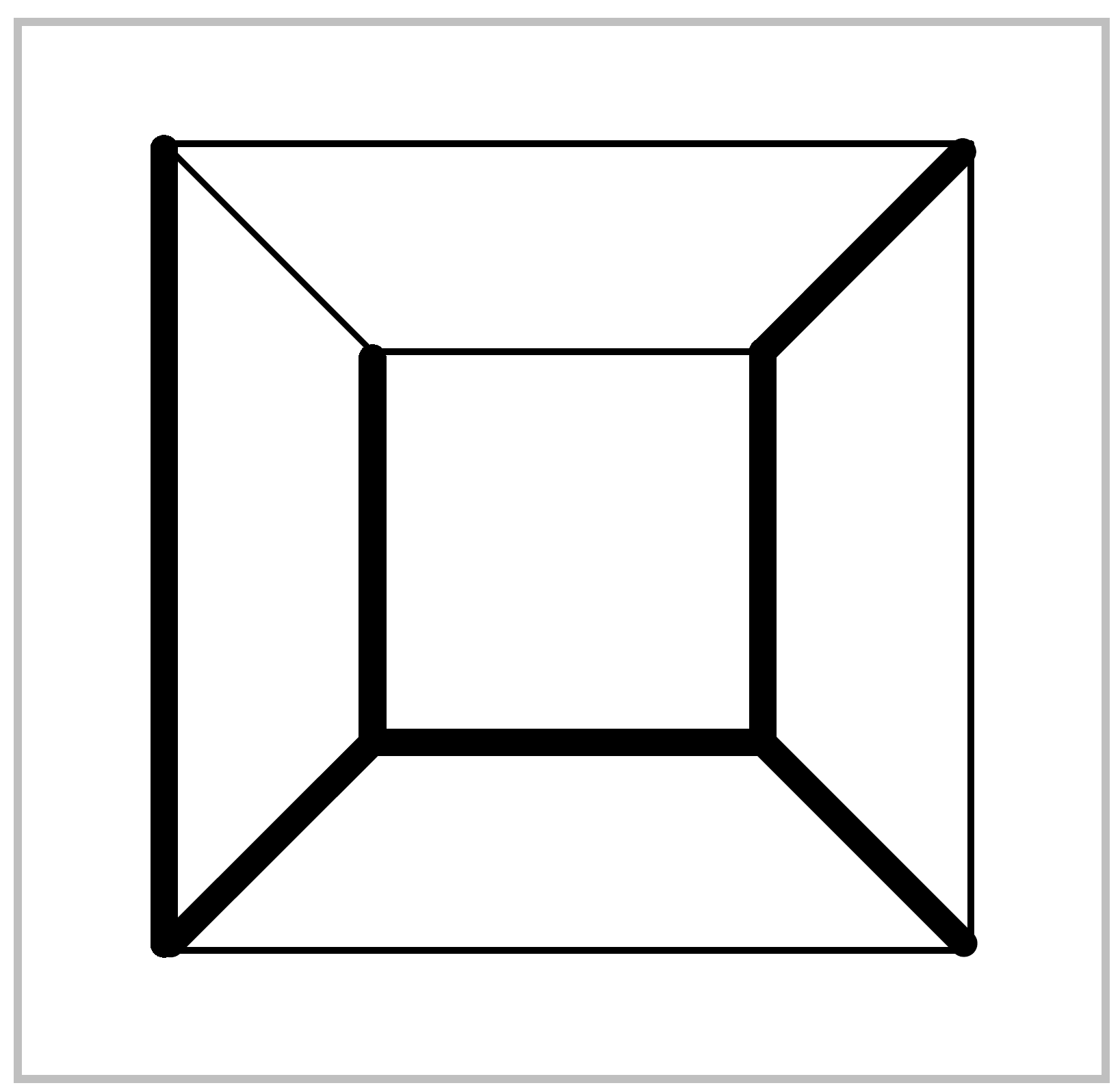

Example 1.22. Let \(X\) be the graph shown in the figure, consisting of the twelve edges of a cube. The seven heavily shaded edges form a maximal tree \(T \subset X\), a contractible subgraph containing all the vertices of \(X\). We claim that \(\pi_1(X)\) is the free product of five copies of \(\mathbb{Z}\), one for each edge not in \(T\). To deduce this from van Kampen’s theorem, choose for each edge \(e_\alpha\) of \(X-T\) an open neighborhood \(A_\alpha\) of \(T \cup e_\alpha\) in \(X\) that deformation retracts onto \(T \cup e_\alpha\). The intersection of two or more \(A_\alpha\)’s deformation retracts onto \(T\), hence is contractible. The \(A_\alpha\)’s form a cover of \(X\) satisfying the hypotheses of van Kampen’s theorem, and since the intersection of any two of them is simply-connected we obtain an isomorphism \(\pi_1(X) \approx {\Large *}_\alpha \pi_1(A_\alpha)\). Each \(A_\alpha\) deformation retracts onto a circle, so \(\pi_1(X)\) is free on five generators, as claimed. As explicit generators we can choose for each edge \(e_\alpha\) of \(X-T\) a loop \(f_\alpha\) that starts at a basepoint in \(T\), travels in \(T\) to one end of \(e_\alpha\), then across \(e_\alpha\), then back to the basepoint along a path in \(T\).

Van Kampen’s theorem is often applied when there are just two sets \(A_\alpha\) and \(A_\beta\) in the cover of \(X\), so the condition on triple intersections \(A_\alpha \cup A_\beta \cup A_\gamma\) is superfluous and one obtains an isomorphism \(\pi_1(X) \approx (\pi_1(A_\alpha) * \pi_1(A_\beta))/N\), under the assumption that \(A_\alpha \cup A_\beta\) is path-connected. The proof in this special case is virtually identical with the proof in the general case, however.

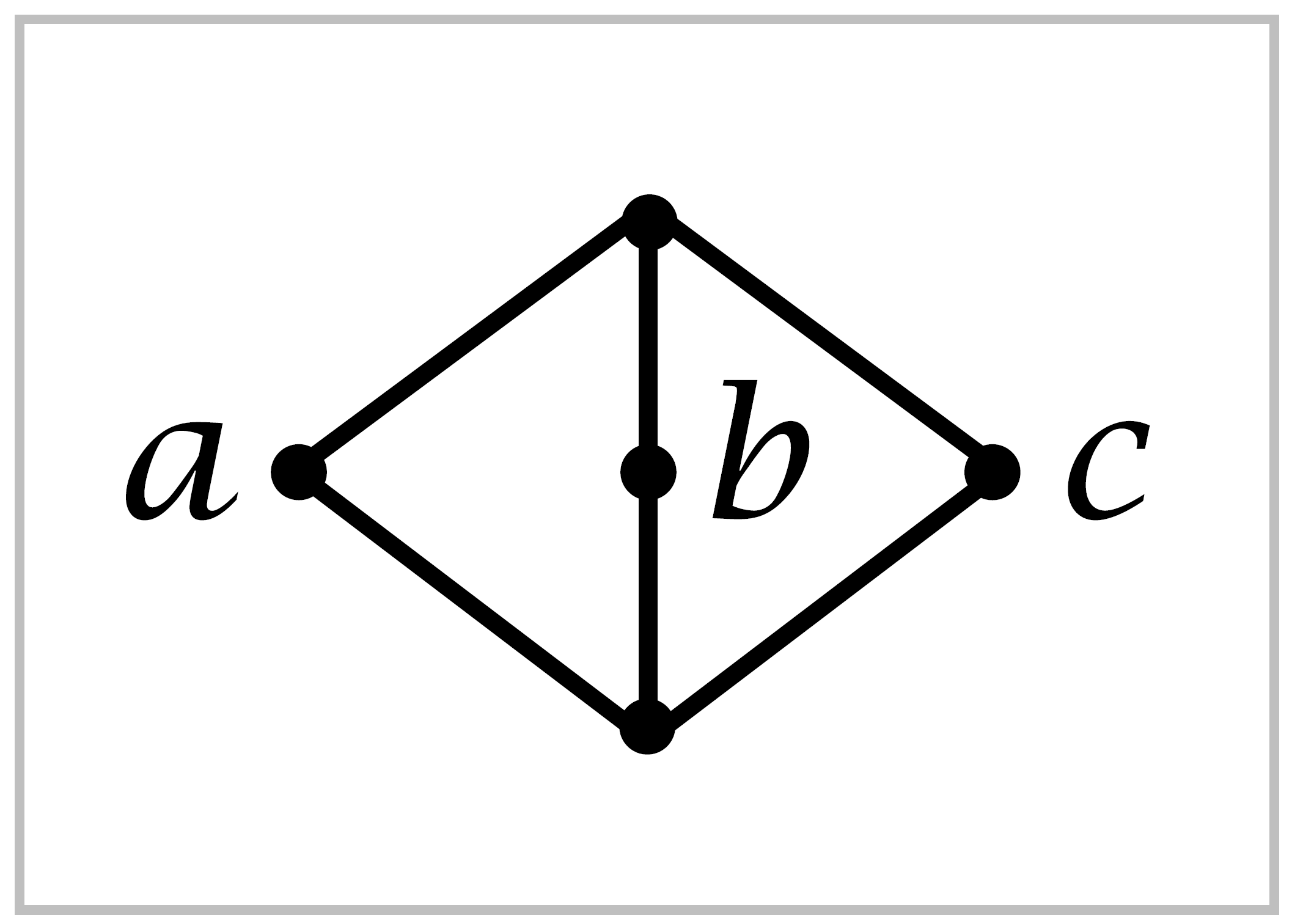

One can see that the intersections \(A_\alpha \cup A_\beta\) need to be path-connected by considering the example of \(S^1\) decomposed as the union of two open arcs. In this case \(\phi\) is not surjective. For an example showing that triple intersections \(A_\alpha \cup A_\beta \cup A_\gamma\) need to be path-connected, let \(X\) be the suspension of three points \(a,\, b,\, c\), and let \(A_\alpha ,\, A_\beta ,\, ` and :math:`A_\gamma\) be the complements of these three points.

The theorem does apply to the covering \(\{A_\alpha, A_\beta\}\), so there are isomorphisms \(\pi_1(X) \approx \pi_1(A_\alpha) * \pi_1(A_\beta) \approx \mathbb{Z}*\mathbb{Z}\) since \(A_\alpha \cup A_\beta\) is contractible. If we tried to use the covering \(\{A_\alpha,A_\beta,A_\gamma\}\), which has each of the twofold intersections path-connected but not the triple intersection, then we would get \(\pi_1(X) \approx \mathbb{Z}*\mathbb{Z}*\mathbb{Z}\), but this is not isomorphic to \(\mathbb{Z}*\mathbb{Z}\) since it has a different abelianization.

Proof of van Kampen’s theorem: We have already proved the first part of the theorem concerning surjectivity of \(\phi\) in Lemma 1.15. To prove the harder part of the theorem, that the kernel of \(\phi\) is \(N\), we first introduce some terminology. By a factorization of an element \([f] \in \pi_1(X)\) we shall mean a formal product \([f_1] \cdot [f_k]\) where:

Each \(f_i\) is a loop in some \(A_\alpha\) at the basepoint \(x_0\), and \([f_i] \in \pi_1(A_\alpha)\) is the homotopy class of \(f_i\).

The loop \(f\) is homotopic to \(f_1 \cdot \cdots f_k\) in \(X\).

A factroization of \([f]\) is thus a word in \({\Large *}_\alpha \pi_1(A_\alpha)\), possibly unreduced, that is mapped to \([f]\) by \(\phi\). Surjectivity of \(\phi\) is equivalent to saying that every \([f] \in \pi_1(X)\) has a factorization.

We will be concerned with the uniqueness of factorizations. Call two factorizations of \([f]\) equivalent if they are related by a sequence of the following two sorts of moves or their inverses:

Combine adjacent terms \([f_i][f_{i+1}]\) into a single term \([f_i \cdot f_{i+1}]\) if \([f_i]\) and \([f_{i+1}]\) lie in the same group \(\pi_1(A_\alpha)\).

Regard the term \([f_i]\in \pi_1 (A_\alpha)\) as lying in the group \(\pi_1(A_\beta)\) rather than \(\pi_1(A_\alpha)\) if \(f_i\) is a loop in \(A_\alpha \cup A_\beta\).

The first move does not change the element of \({\Large *}_\alpha \pi_1 (A_\alpha)\) defined by the factorization. The second move does not change the image of this element in the quotient group \(Q={\Large *}_\alpha \pi_1(A_\alpha)/N\), by the definition of \(N\). So equivalent factorizations give the same element of \(Q\).

If we can show that any two factorizations of \([f]\) are equivalent, this will say that the map \(Q \rightarrow \pi_1(X)\) induced by \(\phi\) is injective, hence the kernel of \(\phi\) is exactly \(N\), and the proof will be complete.

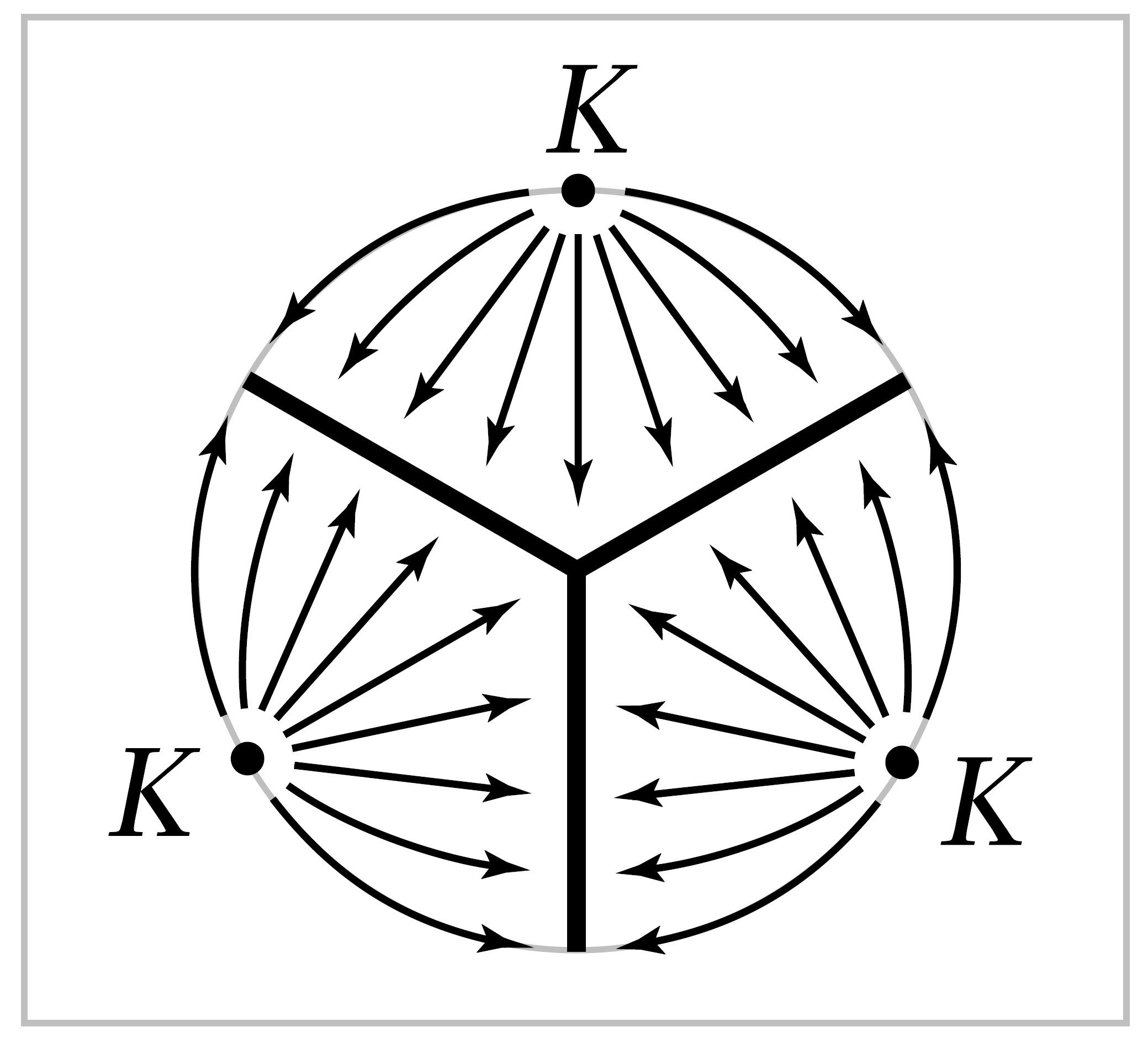

Let \([f_1] \cdots [f_k]\) and \([f'_1] \cdots [f'_l]\) be two factorizations of \([f]\). The composed paths \(f_1 \cdot \cdots \cdot f_k\) and \(f_1'\cdot \cdots \cdot f_l'\) are then homotopic, so let \(F:I\times I \rightarrow X\) be a homotopy from \(f_1 \cdot \cdots \cdot f_k\) to \(f_1' \cdot \cdots \cdot f_l'\). There exist partitions \(0=s_0<s_1<\cdots < s_m = 1\) and \(0 = t_0 < t_1 < \cdots < t_n =1\) such that each rectangle \(R_{ij}=[s_{i-1},s_i]\times [t_{j-1},t_j]\) is mapped by \(F\) into a single \(A_\alpha\), which we label \(A_{ij}\). These partitions may be obtained by covering \(I\times I\) by finitely many rectangles \([a,b] \times [c,d]\) each mapping to a single \(A_\alpha\), using a compactness argument, then partitioning \(I \times I\) by the union of all the horizontal and vertical lines containing edges of theses rectangles.

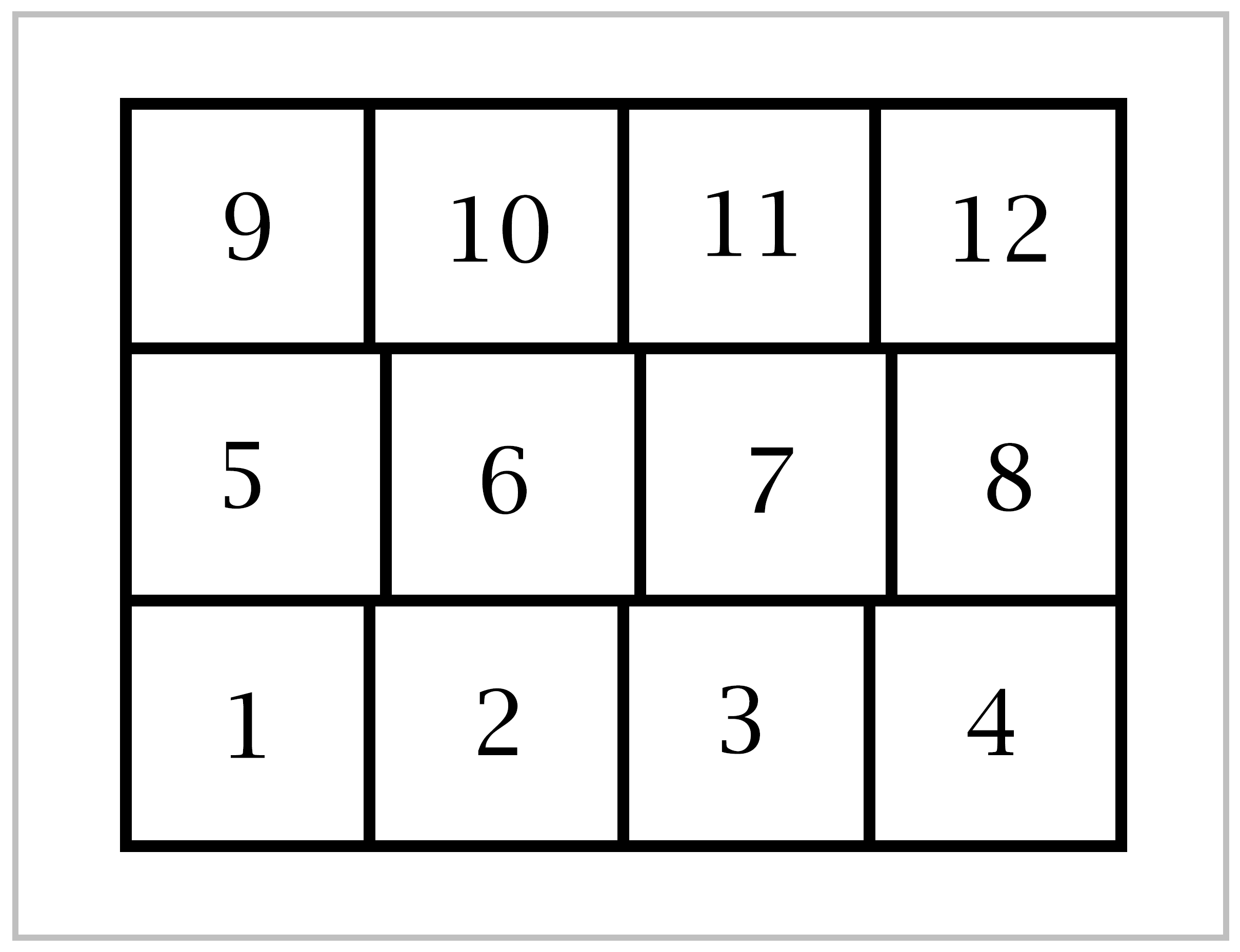

We may assume the \(s\)-partition subdivides the partitions giving the products \(f_1 \cdot \cdots \cdot f_k\) and \(f_1' \cdot \cdots \cdot f_l'\). Since \(F\) maps a neighborhood of \(R_{ij}\) to \(A_{ij}\), we may perturb the vertical sides of the rectangles \(R_{ij}\) so that each point of \(I \times I\) lies in at most three \(R_{ij}\)’s. We may assume there are at least three rwos of rectangles, so we can do this perturbation just on the rectangles in the intermediate rows, leaving the top and bottom rows unchanged. Let us relabel the new rectangles \(R_1,R_2, \cdots ,R_{mn}\), ordering them as in the figure.

If \(\gamma\) is a path in \(I \times I\) from the left edge to the right edge, then the restriction \(F|\gamma\) is a loop at the basepoint \(x_0\) since \(F\) maps both the left and right edges of \(I \times I\) to \(x_0\). Let \(\gamma_r\) be the path separating the first \(r\) rectangles \(R_1, \cdots, R_r\) from the remaining rectangles. Thus \(\gamma_0\) is the bottom edge of \(I \times I\) and \(\gamma_{mn}\) is the top edge. We pass from \(\gamma_r\) to \(\gamma_{r+1}\) by pushing across the rectangle \(R_{r+1}\).

Let us call the corners of the \(R_r\)’s vertices. For each vertex \(v\) with \(F(v) \neq x_0\) we can choose a path \(g_v\) from \(x_0\) to \(F(v)\) that lies in the intersection of the two or three \(A_{ij}\)’s corresponding to the \(R_r`s containing :math:`v\), since we assume the intersection of any two or three \(A_{ij}\)’s is path-connected. Then we obtain a factorization of \([F|\gamma_r]\) by inserting the appropriate paths \(\bar{g}_vg_v\) into \(F|\gamma_r\) at successive vertices, as in the proof of surjectivity of \(\phi\) in Lemma 1.15. This factorization depends on certain choices, since the loop corresponding to a segment between two successive vertices can lie in two different \(A_{ij}\)’s when there are two different rectangles \(R_{ij}\) containing this edge. Different choices of these \(A_{ij}\)’s change the factorization of \([F|\gamma_r]\) to an equivalent factorization, however. Furthermore, the factorizations associated to successive paths \(\gamma_r\) and \(\gamma_{r+1}\) are equivalent since pushing \(\gamma_r\) across \(R_{r+1}\) to \(\gamma_{r+1}\) changes \(F|\gamma_r\) to \(F|\gamma_{r+1}\) by a homotopy within the \(A_{ij}\) corresponding to \(R_{r+1}\), and we can choose this \(A_{ij}\) for all the segments of \(\gamma_r\) and \(\gamma_{r+1}\) in \(R_{r+1}\).

We can arrange that the factorization associated to \(\gamma_0\) is equivalent to the factorization \([f_1] \cdots [f_k]\) by choosing the path \(g_v\) for each vertex \(v\) along the lower edge of \(I \times I\) to lie not just in the two \(A_{ij}\)’s corresponding to the \(R_s\)’s containing \(v\) along the lower edge to lie in the \(A_\alpha\) for the \(f_i\) containing \(v\) in its domain. In case \(v\) is the common end-point of the domains of two consecutive \(f_i\)’s we have \(F(v)=x_0\), so there is no need to choose a \(g_v\) for such \(v\)’s. In similar fashion we may assume that the factorization associated to the final \(\gamma_{mn}\) is equivalent to \([f_1'] \cdots [f_l']\). Since the factorizations associated to all the \(\gamma_r\)’s are equivalent, we conclude that the factorizations \([f_1] \cdots [f_k]\) and \([f_1'] \cdots [f_l']\) are equivalent. ◻

Example 1.23: Linking of Circles. We can apply van Kampen’s theorem to calculate the fundamental groups of three spaces discussed in the introduction to this chapter, the complements in :math:`mathbb{R}^3`of a single circle, two unlinked circles, and two linked circles.

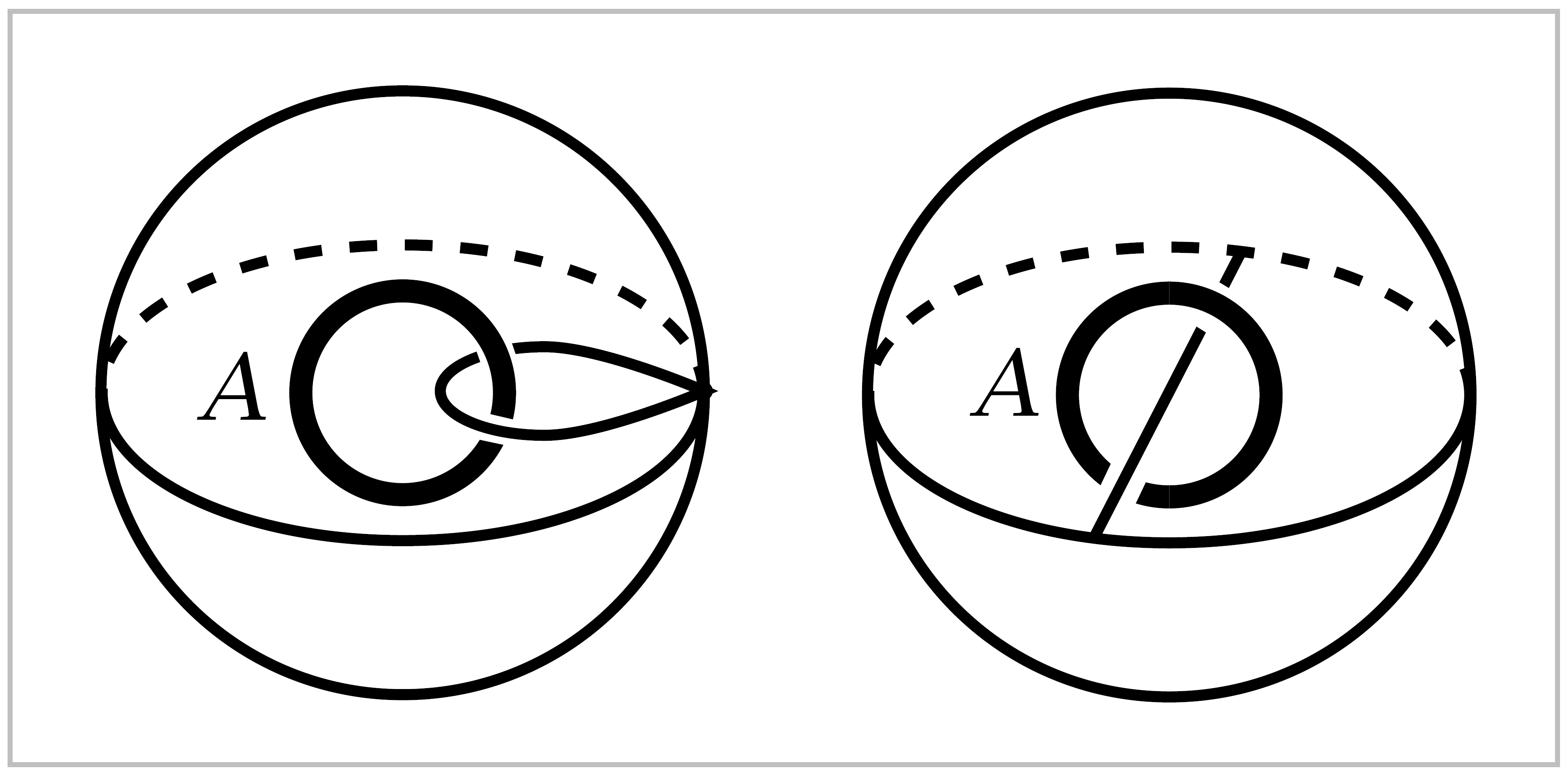

The complement \(\mathbb{R}^3 -A\) of a single circle \(A\) deformation retracts onto a wedge sum \(S^1 \vee S^2\) embedded in \(\mathbb{R}^3 -A\) as shown in the first of the two figures a t the right. It may be easier to see that \(\mathbb{R}^3 - A\) deformation retracts onto the union of \(S^2\) with a diameter, as in the second figure, where points outside \(S^2\) deformation retract onto \(S^2\), and points inside \(S^2\) and not in \(A\) can be pushed away from \(A\) toward \(S^2\) or the diameter. Having this deformation retraction in mind, one can then see how it must be modified if the two endpoints of the diameter are gradually moved toward each other along the equator until they coincide, forming the \(S^1\) summand of \(S^1 \vee S^2\). Another way of seeing the deformation retraction of \(\mathbb{R}^3-A\) onto \(S^1 \vee S^2\) is to note first that an open \(\epsilon\)- neighborhood of \(S^1 \vee S^2\) obvioulsy deformation retracts onto \(S^1 \vee S^2\) if \(\epsilon\) is sufficiently small. Then observe that this neighborhood is homeomorphic to \(\mathbb{R}^3 -A\) by a homeomorphism that is the identity on \(S^1 \vee S^2\). In fact, the neighborhood can be gradually enlarged by homeomorphisms until it becomes all of \(\mathbb{R}^3 - A\).

In any event, once we see that \(\mathbb{R}^3 -A\) deformation retracts to \(S^1 \vee S^2\), then we immediately obtain isomorphisms \(\pi_1(\mathbb{R}^3-A) \approx \pi_1(S^1 \vee S^2) \approx \mathbb{Z}\) since \(\pi_1(S^2)=0\).

In similar fashion, the complement \(\mathbb{R}^3 - (A \cup B)\) of two unlinked circles \(A\) and \(B\) deformation retracts onto \(S^1 \vee S^1 \vee S^2 \vee S^2\), as in the figure to the right. From this we get \(\pi_1(\mathbb{R}^3 - (A \cup B)) \approx \mathbb{Z} * \mathbb{Z}\)

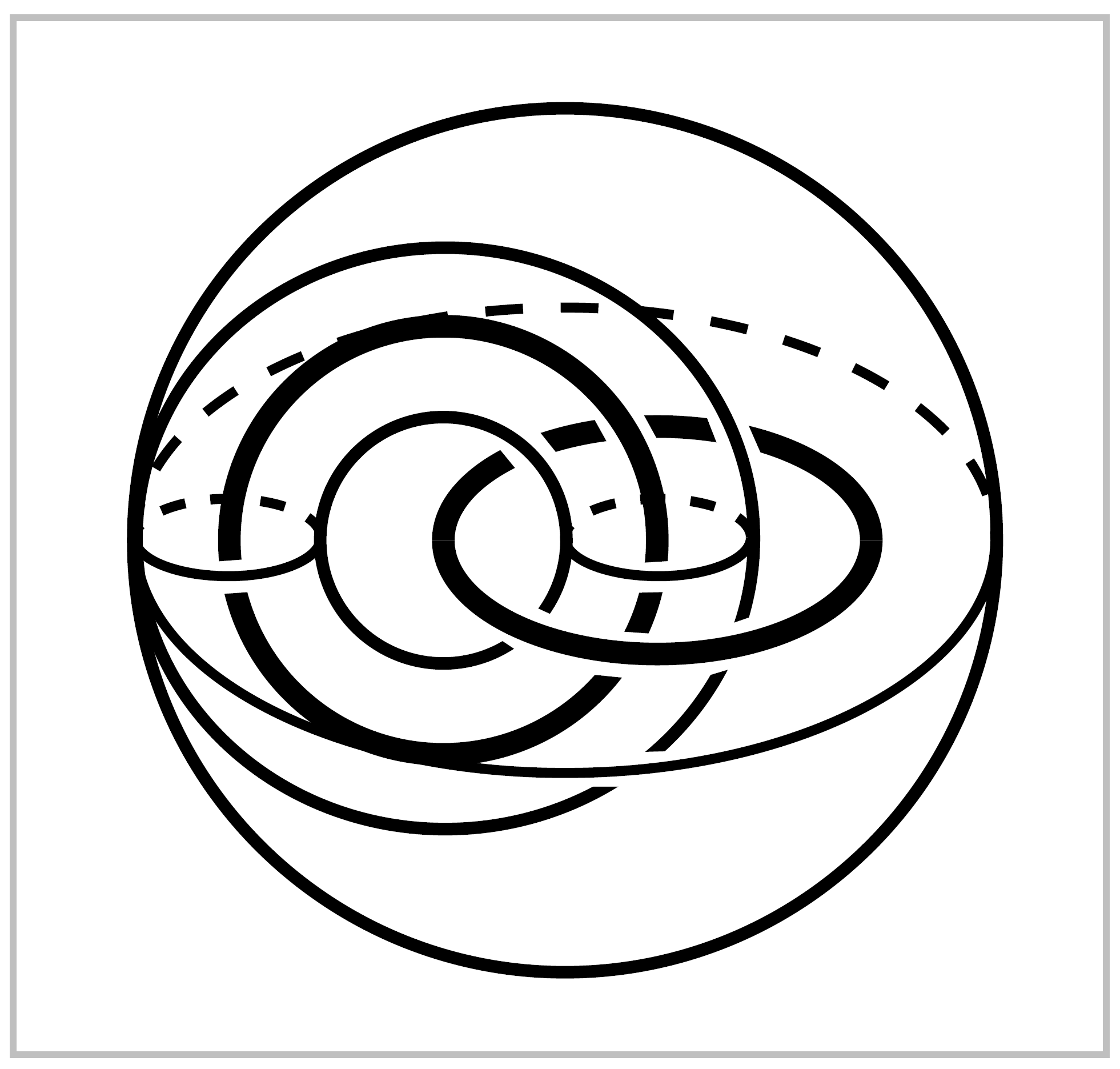

On the other hand, if \(A\) and \(B\) are linked, then \(\mathbb{R}^3 - (A\cup B)\) deformation retracts onto the wedge sum of \(S^2\) and a torus \(S^1 \times S^1\) separating \(A\) and \(B\), as shown in the figure to the left, hence \(\pi_1 (\mathbb{R}^3 - (A \cup B)) \approx \pi_1(S^1 \times S^1) \approx \mathbb{Z} \times \mathbb{Z}\).

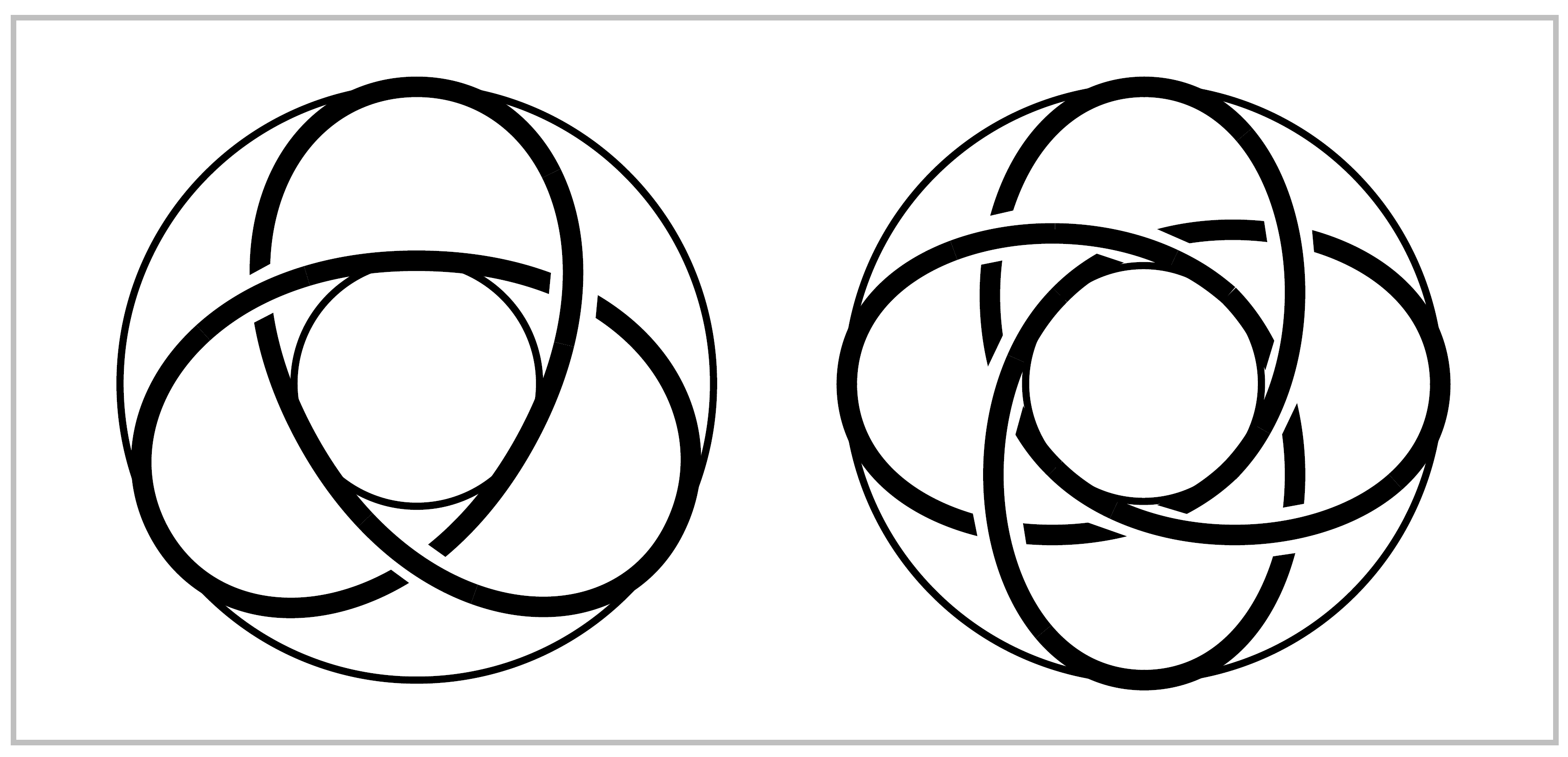

Example 1.24: Torus Knots. For relatively prime positive integers \(m\) and \(n\), the torus knot \(K=K_{m,n} \subset \mathbb{R}^3\) is the image of the embedding \(f:S^1 \rightarrow S^1 \times S^1 \subset \mathbb{R}^3\), \(f(z)=(z^m,z^n)\), where the torus \(S^1 \times S^1\) is embedded in \(\mathbb{R}^3\) in the standard way.

The knot \(K\) winds around the torus a total of \(m\) times in the longitudinal direction and \(n\) times in the meridional direction, as shown in the figure for the case \((m,n)=(2,3)\) and \((3,4)\). One needs to assume that \(m\) and \(n\) are relatively prime in order for the map \(f\) to be injective. Without this assumption \(f\) would be \(d\)-to-\(1\) where \(d\) is the greatest common divisor of \(m\) and \(n\), and the image of \(f\) would be the knot \(K_{m/d,n/d}\). One could also allow negative values for \(m\) or \(n\), but this would only change \(K\) to a mirror-image knot.

Let us compute \(\pi_1(\mathbb{R}^3-K)\). It is slighyl easier to do the calculation with \(\mathbb{R}^3\) replaced by its one-point compactification \(S^3\). An application of van Kampen’s theorem shows that this does not affect \(\pi_1\). Namely, write \(S^3-K\) as the union of \(\mathbb{R}^3-K\) and an open ball \(B\) formed by the compactification point together with the complement of a large closed ball in \(\mathbb{R}^3\) containing \(K\). Both \(B\) and \(B \cap (\mathbb{R}^3-K)\) are simply-connected, the latter space being homeomorphic to \(S^2 \times \mathbb{R}\). Hence van Kampen’s theorem implies that the inclusion \(\mathbb{R}^3-K \hookrightarrow S^3 -K\) induces an isomorphism on \(\pi_1\).

We compute \(\pi_1(S^3 - K)\) by showing that it deformation retracts onto a \(2\)-dimensional complex \(X=X_{m,n}\) homeomorphic to the quotient space of a cylinder \(S^1 \times I\) under the identifications \((z,0) ~ (e^{2\pi i / m}z,0)\) and \((z,1)~(e^{2\pi i/n}z,1)\). If we let \(X_m\) and \(X_n\) be the two halves of \(X\) formed by the quotients of \(S^1 \times [0, \frac{1}{2}]\) and \(S^1 \times [\frac{1}{2}, 1]\), then \(X_m\) and \(X_n\) are the mapping cylinders of \(z \mapsto z^m\) and \(z \mapsto z^n\). The intersection \(X_m \cup X_n\) is the circle \(S^1 \times \{\frac{1}{2}\}\), the domain end of each mapping cylinder.

To obtain an embedding of \(X\) in \(S^3 - K\) as a deformation retract we will use the standard decomposition of \(S^3\) into to solid tori \(S^1 \times D^2\) and \(D^2 \times S^1\), the result of regarding \(S^3\) as \(\partial D^4 = \partial(D^2 \times D^2) = \partial D^2 \times D^2 \cup D^2 \times \partial D^2\). Geometrically, the first solid torus \(S^1 \times D^2\) can be identified with the compact region in \(\mathbb{R}^3\) bounded by the standard torus \(S^1 \times S^1\) containing \(K\), and the second solid torus \(D^2 \times S^1\) is then the closure of the complement of the first solid torus, together with the compactification point at infinity. Notice that meridional circles in \(S^1 \times S^1\) bound disks in the first solid torus, while it is longitudinal circles that bound disks in the second solid torus.

In the first solid torus, \(K\) intersects each of the meridian circles \(\{x\} \times \partial D^2\) in \(m\) equally spaced points, as indicated in the figure at the right, which shows a meridian disk \(\{x\} \times D^2\). These \(m\) points can be separated by a union of \(m\) radial line segments. Letting \(x\) vary, these radial segments then trace out a copy of the mapping cylinder \(X_m\) in the first solid torus. Symmetrically, there is a copy of the other mapping cylinder \(X_n\) in the second solid torus. The complement of \(K\) in the first solid torus deformation retracts onto \(X_m\) by flowing within each meridian disk as shown. In similar fashion the complement of \(K\) in the second solid torus deformation retracts onto \(X_n\). These two deformation retractions do not agree on their common domain of definition \(S^1 \times S^1 - K\), but this is easy to correct by distorting the flows in the two solid tori so that in \(S^1 \times S^1 -K\) both flows are orthogonal to \(K\). After this modification we now have a well-defined deformation retraction of \(S^3-K\) onto \(X\). Another way of describing the situation would be to say that for an open \(\epsilon\)-neighborhood \(N\) of \(K\) bounded by a torus \(T\), the complement \(S^3-N\) is the mapping cylinder of a map \(T \rightarrow X\).

To compute \(\pi_1(X)\) we apply van Kampen’s theorem to the decomposition of \(X\) as the union of \(X_m\) and \(X_n\), or more properly, open neighborhoods of these two sets that deformation retract onto them. Both \(X_m\) and \(X_n\) are mapping cylinders that deformation retract onto circles, and \(X_m \cup X_n\) is a circle, so all three of these spaces have fundamental group \(\mathbb{Z}\). A loop in \(X_m \cup X_n\) representing a generator of \(\pi_1(X_m \cup X_n)\) is homotopic in \(X_m\) to a loop representing \(m\) times a generator, and in \(X_n\) to a loop representing \(n\) times a generator. Van Kampen’s theorem then says that \(\pi_1(X)\) is the quotient of the free group on generators \(a\) and \(b\) obtained by factoring out the normal subgroup generated by the element \(a^mb^{-n}\).

Let us denote by \(G_{m,n}\) this group \(\pi_1(X_{m,n})\) defined by two generators \(a\) and \(b\) and one relation \(a^m = b^n\). If \(m\) or \(n\) is \(1\), then \(G_{m,n}\) is infinite cyclic since in these cases the relation just expresses one generator as a power of the other. To describe the structure of \(G_{m,n}\) when \(m,n>1\) let us first compute the center of \(G_{m,n}\), the subgroup consisting of elements that commute with all elements of \(G_{m,n}\). The element \(a^m=b^n\) commutes with \(a\) and \(b\), so the cyclic subgroup \(C\) generated by this element lies in the center. In particular, \(C\) is a normal subgroup, so we can pass to the quotient group \(G_{m,n} /C\), which is the free product \(\mathbb{Z}_m * \mathbb{Z}_n\). According to Exercise 1 at the end of this section, a free product of nontrivial groups has trivial center. From this it follows that \(C\) is exactly the center of \(G_{m,n}\). As we will see in Example 1.44, the elements \(a\) and \(b\) have infinite order in \(G_{m,n}\), so \(C\) is infinite cyclic, but we will not need this fact here.

We will show now that the integers \(m\) and \(n\) are uniquely determined by the group \(\mathbb{Z}_m * \mathbb{Z}_n\), hence also by \(G_{m,n}\). The abelianization of \(\mathbb{Z}_m * \mathbb{Z}_n\) is \(\mathbb{Z}_m \times \mathbb{Z}_n\), of order \(mn\) , so the product \(mn\) is uniquely determined by \(\mathbb{Z}_m * \mathbb{Z}_n\). To determine \(m\) and \(n\) individually, we use another assertion from Exercise 1 at the end of the section, that all torsion elements of \(\mathbb{Z}_m * \mathbb{Z}_n\) are conjugate to elements of one of the subgroups \(\mathbb{Z}_m\) and \(\mathbb{Z}_n\), hence have order dividing \(m\) or \(n\). Thus the maximum order of torsion elements of \(\mathbb{Z}_m * \mathbb{Z}_n\) is the larger of \(m\) and \(n\). The larger of these two numbers is therefore uniquely determined by the group \(\mathbb{Z}_m * \mathbb{Z}_n\), hence also the smaller since the product is uniquely determined.

The preceding analysis of \(\pi_1(X_{m,n})\) did not need the assumption that \(m\) and \(n\) are relatively prime, which was used only to realte \(X_{m,n}\) to torus knots. An interesting fact is that \(X_{m,n}\) can be embedded in \(\mathbb{R}^3\) only when \(m\) and \(n\) are relatively prime. This is shown in the remarks following Corollary 3.46. For example, \(X_{2,2}\) is the Klein bottle since it is the union of two copies of the Möbius band \(X_2\) with their boundary circles identified, so this nonembeddability statement generalizes the fact that the Klein bottle cannot be embedded in \(\mathbb{R}^3\).

An algorithm for computing a presentation for \(\pi_1(\mathbb{R}^3 - K)\) for an arbitrary smooth or piecewise linear knot \(K\) is described in the exercises, but the problem of determining when two of these fundamental groups are isomorphic is generally much more difficult than in the special case of torus knots.

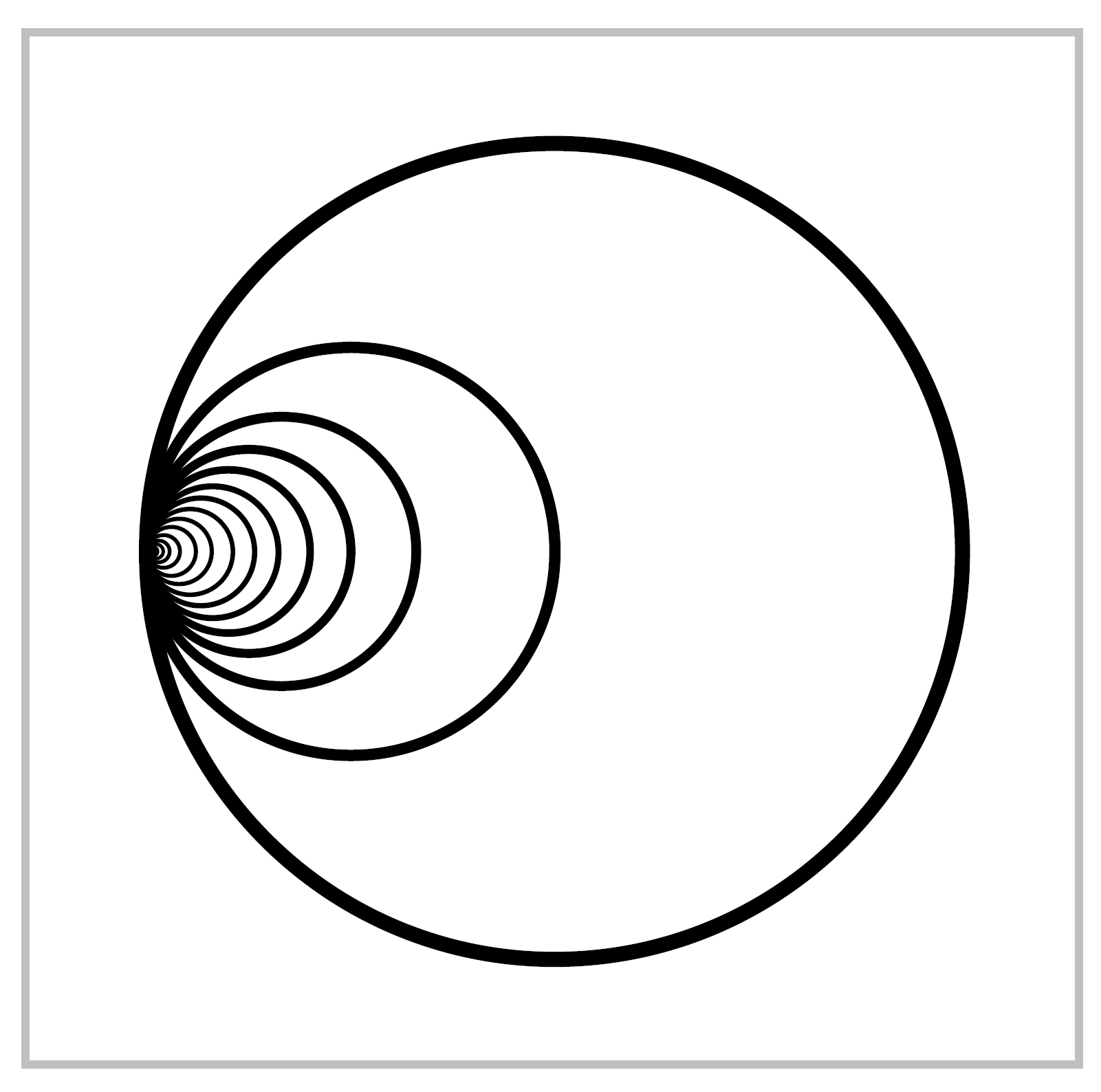

Example 1.25: The Shrinking Wedge of Circles. Consider the subspace \(X \subset \mathbb{R}^2\) that is the union of the circles \(C_n\) of radius \(\frac{1}{n}\) and center \((\frac{1}{n}, 0)\) for \(n=1,2, \cdots\). At first glance one might confuse \(X\) with the wedge sum of an infinite sequence of circles, but we will show that \(X\) has a much larger fundamental group than the wedge sum. Consider the retractions \(r_n : X \rightarrow C_n\) collapsing all \(C_i\)’s except \(C_n\) to the origin. Each \(r_n\) induces a surjection \(\rho _n : \pi_1(X) \rightarrow \pi_1(C_n) \approx \mathbb{Z}\), where we take the origin as the basepoint. The product of the \(\rho_n\)’s is a homomorphism \(\rho :\pi_1(X) \rightarrow \prod _\infty \mathbb{Z}\) to the direct product (not the direct sum) of infinitely many copies of \(\mathbb{Z}\), and \(\rho\) is surjective since for every sequence of integers \(k_n\) we can construct a loop \(f:I\rightarrow X\) that wraps \(k_n\) times around \(C_n\) in the time interval \([1-\frac{1}{n},1-\frac{1}{n+1}]\). This infinite composition of loops is certainly continuous at each time less than \(1\), and it is continuous at time \(1\) since every neighborhood of the basepoint in \(X\) contains all but finitely many of the circles \(C_n\). Since \(\pi_1(X)\) maps onto the uncountable group \(\prod_\infty \mathbb{Z}\), it is uncountable. On the other hand, the fundamental group of a wedge sum of countably many circles is countably generated, hence countable.

The group \(\pi_1(X)\) is actually far more complicated than \(\prod_\infty \mathbb{Z}\). For one thing, it is nonabelian, since the retraction \(X \rightarrow C_1 \cup \cdots \cup C_n\) that collapses all the circles smaller than \(C_n\) to the basepoint induces a surjection from \(\pi_1(X)\) to a free group on \(n\) generators. For a complete description of \(\pi_1(X)\) see [Cannon & Conner 2000].

It is a theorem of [Shelah 1988] that for a path-connected, locally path-connected compact metric space \(X\), \(\pi_1(X)\) is either finitely generated on uncountable.